02 May 2007

Questing Press Meets Fortress Bush

Where, in a strange twist of fate, the White House press corps is played by King Arthur and his Knights ... and Fortress Bush is French!!

"Back ‘em up, starve ‘em down, and drive up their negatives."

Incentives, Votes, a Veto and We Start All Over Again

Bush Makes Right Move on Veto, says American Legion

"The American Legion is glad that the president vetoed this irresponsible legislation but saddened that Congress let it get this far," [The National Commander of The American Legion Paul A. Morin] said. "First the House passed a blueprint for disaster and then the Senate passed a recipe for surrender. There can only be one commander in chief and he should be the one to determine when the mission is complete."VFW Urges Reid to Stop Defeatist Rhetoric

“You can’t support the troops without supporting what it is they do, which in a combat zone means the mission, the mission, the mission,” [Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Commander-in-Chief Gary Kurpius, a Vietnam veteran from Anchorage, Alaska] said.Show Our Troops the Money

Our troops operate in a world of ideals known as service, commitment and sacrifice. They don't do politics, but they do know when they are being abandoned, such as when Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D., Nev.) said he would introduce legislation to provide funding for certain aspects of the war, but not for combat operations.

Not funding direct combat operations is the same as having your hands tied in a knife fight. And while some may regard the rhetoric as normal political-speak, our troops are taking it personally, because they know that not being allowed to take the fight directly to the enemy is exactly what happened in Korea and Vietnam. They don't want to repeat history.

Malware meets Robot Genius

via c|net News:

[Robot Genius] claims that Spyberus has a 99 percent success rate in reversing spyware, adware, rootkits, and other forms of malicious software. Free trial versions of RGcrawler Data and Spyberus are available now on Robot Genius' Web site; RGguard is "coming soon."

01 May 2007

Dog Bites Man III

Three days ago, Former Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist was cleared of insider trading allegations based on his 2005 sale of HCA Inc. stock.

Still no word at the New York Times.

Don't hold your breath ...

... or if you're Frank Rich, please do.

After last weekend’s correspondents’ dinner, The Times decided to end its participation in such events.Riiiiiiight.

After reading Rich's screed, I first wondered why anyone would intentionally pull any of the irrelevant New York Times columnists out from behind their self-imposed pay-wall. Then it occurred to me that if a Times columnist writes something with enough heat (pathos) - even if completely lacking in logos or ethos - it just might be deemed good enough by some partisan website/blog to be reprinted in the public sphere.

It's a reverse-gatekeeper function!

Even more disappointing is Jay Rosen's post at his recently neglected PressThink blog. After complaining about Bush breaking the consensus and not playing by long established rules with the press, he tosses out this gem:

Still, Rutenberg didn’t violate any of the rules for interviewing sources, and I knew what I was getting into when I called him back. Reporter and I talk for 30 to 45 minutes; he decides which twelve seconds he wants to use. If he has a pre-existing narrative that he wants me to ratify, chances are good I will say something he can use to do just that. Them’s the rules.See? The compliant and slow-to-catch-on press that has been busily selecting 12 second sound bites to validate their own pre-existing narratives during the first six years of the Bush administration were in fact overwhelmed!

"I told Rutenberg that I did not see the press as "in the pocket of Bush" (as many on the left do) but as overwhelmed by the phenomena of Bush-as-president, and by the radicalism of his Administration, especially the expansion of executive power."Now that would be an interesting PressThink post. How does a press, blinded by an "objective process" that includes splicing sound bites and anonymous sources together in order to validate their own pre-existing narratives, get "run over" by a President?

[Journalists] were unable to think politically about their own institution, but they could go on for quite a while about the separation between news and opinion sections.Related: History of the White House Correspondents’ Association

The WHCA lay dormant until 1920 when the organization held its first dinner. In 1924, Calvin Coolidge became the first of 13 presidents to attend the dinner.UPDATE: Edited for clarity.

Until World War II, the annual dinner was an entertainment extravaganza, featuring singing between courses, a homemade movie and an hour-long, post-dinner show with big-name performers.

30 April 2007

Bloggers, the NYT and Quality

While we should give reporter Kirk Semple kudos for actually traveling to Anbar to get the story, several bloggers have been on the ground consistently over the last year, and producing major stories to rival the quality of the NYT.

29 April 2007

The Surge as Stabilty and Support

During the Clinton administration, there was a debate over the primacy of stability and support operations and their impact on military readiness. The military was being significantly downsized, while at the same time, sent on an increasing number of these type of operations that committed us to rotating troops there for years. [See Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798-2001 (157KB pdf). It is not a complete list of military deployments. For example, not included on this list is Operation Safe Border/UN Military Observer Mission Ecuador - Peru which began in 1995 and ended in 1999. I do not know how many other deployments did not make the list, but it's probably more than just that one.]

This debate, famously articulated by former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright ("What's the point of having this superb military that you've always been talking about if we can't use it?" - here and here) and again as the "Clinton Doctrine" ... was not a new debate. As Gen. John M. Shalikashvili explained to the Robert R. McCormick Tribune Foundation, George Washington University, Washington, May 4, 1995:

But the debate has changed in one way. During the Cold War it was those on the left criticizing the Cold Warriors for taking too many risks; for overcommitting our lives, our treasures and our morality; for overextending our power and our commitments for the purpose of containing communism. Today, of course, that is different. It is those on the right who are castigating those on the left for allowing their humanitarian and their moral impulses to places where our interests, in fact, are thin or nonexistent. So the core debate has not ended at all. The real issues have not been resolved. Only the tables have been turned. [emphasis added]Military force structure during the Clinton administration was being driven by a sense that after the end of the Cold War, "everything's changed". The basis for our military force structure before the end of the Cold War was our national security requirement to fight and win two regional wars (2MTW). The 2MTW concept was discarded as archaic Cold War thinking. We no longer needed to structure the military to fight one "high-intensity" conflict [Fulda Gap] and one "medium-intensity" conflict [Korea or Iraq] simultaneously. We no longer perceived a threat from an adversary that could fight a "high-intensity" war. Instead, we wanted a "peace dividend". We wanted a smaller military. We wanted a balanced budget.

So the risk assessment for the threats to the nation evolved. Instead of simultaneously fighting and winning a high-intensity and a medium-intensity conflict, it became two medium-intensity conflicts. Then it became two "near simultaneous" medium-intensity conflicts: win in one and hold in the other. Asymmetrical warfare and transformation became the cause célèbre in force structure policy. Transformationalists wanted a versatile military that could do everything - using technology as a force multiplier - and be deployable from the U.S. to anywhere in the world (meaning lighter and more modular). American bases abroad became another anachronism of Cold War thinking. For additional insight into how transformation influences force structure planning, I recommend Col. Wolborsky's Swords Into Stilettos: The Battle Between Hedgers and Transformers for the Soul of DoD (219KB pdf) and Tom Barnett's Op/Ed for The Command post.

A useful metaphor for understanding American foreign policy during the 90s and the restructuring of our military forces, as well as their employment throughout the world, is Time's Arrow:

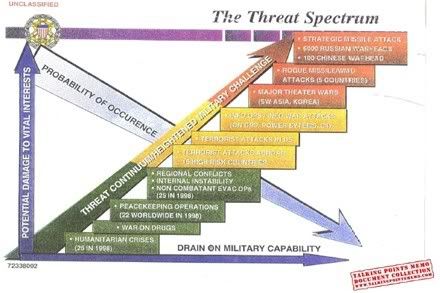

In the post-Cold War era, there has also been a renewed emphasis on time's arrow in the international system against the backdrop of unique trends such as those concerning global transparency and global environment. These trends are the cumulative results of the forces unleashed by the revolutions in communications, information, transportation, and technology that predated the end of the Cold War. Theorists as early as the 1970s argued that with the expansion of commerce as a result of these forces and trends, relationships based on cooperation and integration were becoming at least as important as traditional geopolitical competition. In the intervening years, liberal analysts have concluded that the unique, linear evolution of complex economic interdependence fosters peace by causing trading to be more profitable than war. Interdependent states, in other words, would rather trade than invade--a conclusion at the systems level of analysis for these theorists reinforced by the cumulative learning at the individual and state levels focused on changing values and what is perceived as the irreversible victory of liberal capitalism. From this perspective, war is a particularly counterproductive way for any rational nation-state to achieve the central goals of prosperity and economic growth.[49]In April 2004, Josh Marshall linked to the Threat Spectrum shown below (click for larger view, 273KB pdf).

It is, however, a perspective that overreacts to forces and trends in time's arrow while ignoring the immediate and long-term implications of time's cycle. In the short-term, it is not economic interdependence that has brought about great power peace. Instead, it was the bipolar peace of the Cold War, founded on rivalry and fear of nuclear war, not desire for profit, that induced the cooperation that made economic interdependence safe and therefore possible. In a world in which there is little likelihood of large-scale conflict, states are less concerned about the dependencies that such interdependence creates and about the relative economic disadvantages that open markets produce.[50] At the same time, as leaders in the current transition period react to a variety of "unique" ethnic and religious strife throughout the globe, the Cold War is a useful reminder that during the superpower stability of that long twilight conflict, no such condition occurred for very long in the so-called Third World, a categorization of nation-states that even owed its origins to the bipolar nature of the international system. In that world, the absence of superpower war was not synonymous with global peace; nor was the absence of system transformation through war translated into global stability. Instead, recurrent violence in an unstable "peripheral" system occurred alongside a stable "central" system, with an estimated 127 wars and over 21 million war-related deaths taking place in the developing world during the Cold War.[51]

Marshall's purpose at the time was to demonstrate that terrorism was a known threat prior to Sept. 11, 2001. Relevant to this debate is Marshall's statement:

This is a strategic argument about where our chief vulnerabilities are and where and how our defense resources should be applied -- not a question of who saw what Presidential Daily Brief or what was contained in it.This chart has, in fact, been around for years. You can see on the chart that statistical information is for 1998. Sen. Levin referred to it in 2000 as a document prepared in 1999:

Last year, the Joint Chiefs prepared a diagram demonstrating the full spectrum of threats to our nation's security and prioritizing the probability of occurrence of these various threats. This threat spectrum demonstrated that the threats which carry the greatest potential damage to our vital interests, such as strategic missile attack and major theater wars, are also the least likely to occur. The more likely threats to our national interests will come from regional conflicts due to ethnic, religious or cultural differences, or from terrorism.The Threat Spectrum was referred to again during the 2001 missile defense debate. For example, during Senate Armed Services Committee testimony on July 12, 2001, by then Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz and Lieutenant General Ron Kadish and again by Ted Koppel during an interview with Wolfowitz on July 24, 2001. All of these instances precede the Sept. 10, 2001, reference by Senator Biden that Marshall quotes.

My purpose for using the Threat Spectrum is three-fold: 1) The document has bona fides, as demonstrated by these references; 2) It is an excellent visual for thinking about how to size and structure the force to defeat threats that are considered a low probability of occurence, but high drain on military capability versus more likely threats; and 3) It visually makes a sharp contrast with models used during the Cold War.

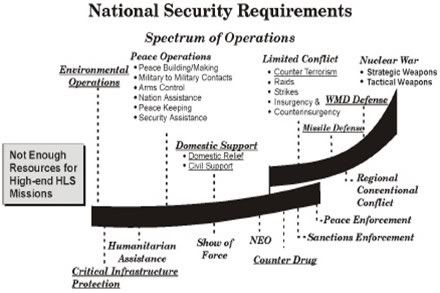

For example, compare the Threat Spectrum with the Spectrum-of-Conflict Model (shown below).

This was a predecessor to the Threat Spectrum and described in Assessing New Missions.

The spectrum-of-conflict model was used in a number of DOD publications and briefings during the Cold War, particularly during the 1980s.What I find instructive, in contrasting the two charts above, is how thinking about military contingencies become more detailed - more complex - after the Cold War ended. How does the military need to be structured based on the type and probability of these diverse threats? What skills are needed to fight and win across the Threat Spectrum?

...

On the surface, the spectrum-of-conflict model is an understandable, idealized representation of the frequency that military force might be used in differing but related activities. Out of context, it could be swiftly dismissed as merely academic, a clever illustration. But, in reality, its use to describe U.S. military activities illustrates specific assumptions about how military power should be used, as well as specific sets of priorities for the missions that the military is designed to carry out.

In March 2001, Lieutenant Colonel Antulio J. Echevarria II wrote a prescient monograph, The Army and Homeland Security: A Strategic Perspective, "investigat[ing] the Army’s role in homeland security from a strategic, rather than a legal or procedural perspective." The reason I find this monograph important is, before Sept. 11, 2001, Homeland Security (HLS) was not a contingency or "threat" that got much visibility. There was an assumption, based on conventional wisdom, that the battle would be fought abroad.

Some key graphs from Echevarria's monograph:

... policymakers must now focus as much on possibilities as on probabilities, as much on vulnerabilities as on threats. Put differently, an effective homeland defense might require treating vulnerabilities as seriously as confirmed threats under the traditional reckoning.One more chart, also from Echevarria's monograph. Take note of the list (spectrum) of operations our military currently performs:

...

In the absence of an authoritative definition, the Army has rightly developed and tentatively approved the following “all-hazards” definition in its HLS: Strategic Planning Guidance (Draft dated Jan. 8, 2001):Protecting our territory, population, and infrastructure at home by deterring, defending against, and mitigating the effects of all threats to US sovereignty; supporting civil authorities in crisis and consequence management; and helping to ensure the availability, integrity, survivability, and adequacy of critical national assets.

Dag Hammarskjold, former UN Secretary-General, said, "Peacekeeping is not a soldier's job, but only a soldier can do it." Perhaps it's the same with stability and support operations such as nation building, which often goes hand-in-hand with peacekeeping. Promoting tolerance and democracy after defeating an intolerant dictator may not be a soldier's job, but soldiers have always been the ones called upon to do it.

Previous:

The Surge as Foreign Internal Defense

Would Sun Tzu Surge?

Si vis pacem, para bellum

Iraq v2.0

The Surge as Foreign Internal Defense

We didn't have the right troops in Iraq after Saddam's regime fell because we didn't have a single, coordinated plan across government agencies - and with our allies and international non-government organizations - for filling the vacuum and stabilizing Iraq that was ready to implement. As a result, we failed to interdict, and were slow to react to, the insurgency by Baathist remnants and the influx of jihadist terrorists. We've been playing catch-up ever since.

President Bush stated the strategic plan at the United States Army War College on May 24, 2004, more than a year after declaring major combat ended:

There are five steps in our plan to help Iraq achieve democracy and freedom. We will hand over authority to a sovereign Iraqi government, help establish security, continue rebuilding Iraq's infrastructure, encourage more international support, and move toward a national election that will bring forward new leaders empowered by the Iraqi people.This plan had two thrusts, political and military, and they were not independent of each other. The political process consisted of interim sovereignty, elections for a transitional national assembly which drafted a constitution, put the draft constitution to the Iraqi people in a referendum in 2005 and elected a permanent government by December 2005.

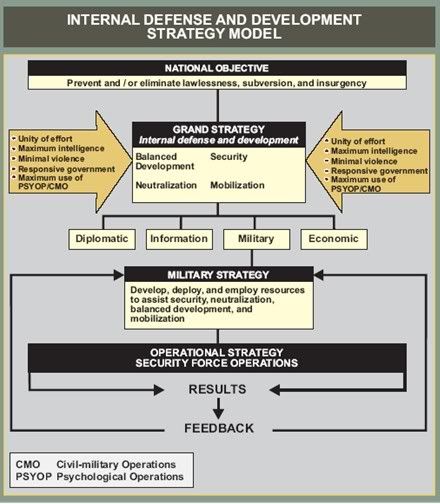

The military thrust is foreign internal defense (Joint Publication 3-07.1, Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Foreign Internal Defense (FID),1.6MB pdf), which includes, but not limited to, counterinsurgency, training security forces, rebuilding infrastructure and, as a result, maintain the host nation's (HN) sovereignty and legitimacy. The graphic at right (click for larger image) shows how military FID strategy is determined by the HN's Internal Defense and Development (IDAD) planning. In order for us to judge the type and number of troops needed, we can look to Chapter III of JP 3-07.1, which lists planning imperatives for FID [all emphasis in original, unfamiliar acronyms expanded in brackets]:

The military thrust is foreign internal defense (Joint Publication 3-07.1, Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Foreign Internal Defense (FID),1.6MB pdf), which includes, but not limited to, counterinsurgency, training security forces, rebuilding infrastructure and, as a result, maintain the host nation's (HN) sovereignty and legitimacy. The graphic at right (click for larger image) shows how military FID strategy is determined by the HN's Internal Defense and Development (IDAD) planning. In order for us to judge the type and number of troops needed, we can look to Chapter III of JP 3-07.1, which lists planning imperatives for FID [all emphasis in original, unfamiliar acronyms expanded in brackets]: - Maintain HN Sovereignty and Legitimacy. If US military efforts in support of FID do anything to undermine the sovereignty or legitimacy of the HN government, then they have effectively sabotaged the FID program. The FID program is only as successful as the HNs IDAD program.

- Understand long-term or strategic implications and sustainability of all US assistance efforts before FID programs are implemented. This is especially important in building HN development and defense self-sufficiency, both of which may require large investments of time and materiel. Comprehensive understanding and planning will include assessing the following:

- The end state for development.

- Sustainability of development programs and defense improvements.

- Acceptability of development models across the range of HN society, and the impact of development programs on the distribution of resources within the HN.

- Second-order and third-order effects of socio-economic change.

- The relationship between improved military forces and existing regional, ethnic, and religious cleavages in society.

- The impact of improved military forces on the regional balance of power.

- Personnel life-cycle management of military personnel who receive additional training.

- The impact of military development and operations on civil-military relations in the HN.

- Tailor military support of FID programs to the environment and the specific needs of the supported HN. Consider the threat as well as local religious, social, economic, and political factors when developing the military plans to support FID. Overcoming the tendency to use a US frame of reference is important because this potentially damaging viewpoint can result in equipment, training, and infrastructure not at all suitable for the nation receiving US assistance.

- Ensure Unity of Effort. As a tool of US foreign policy, FID is a national-level program effort that involves numerous USG [US Government] agencies that may play a dominant role in providing the content of FID plans. Planning must coordinate an integrated theater effort that is joint, interagency, and multinational in order to reduce inefficiencies and enhance strategy in support of FID programs. An interagency political-military plan that provides a means for achieving unity of effort among USG agencies is described in Appendix D, Illustrative Interagency Political-Military Plan for Foreign Internal Defense.

- Understand US Foreign Policy. NSC [National Security Council] directives, plans, or policies are the guiding documents. If those plans are absent, JFCs [Joint Force Commanders] and their staffs must find other means to understand US foreign policy objectives for a HN and its relation to other foreign policy objectives. They should also bear in mind that these relations are dynamic, and that US policy may change as a result of developments in the HN or broader political changes in either country.

FID in Iraq supports the process of midwifing an Iraqi government which is seen as legitimate by the Iraqi people. The size of the force must be small enough, and its employment restricted enough, to make it incumbent on the Iraqi people to accept responsibility for their security.

The military mission has not changed.

Previous:

Would Sun Tzu Surge?

Si vis pacem, para bellum

Iraq v2.0

Would Sun Tzu Surge?

Sun Tzu, Art of War

Thus we may know that there are five essentials for victory: (1) He will win who knows when to fight and when not to fight. (2) He will win who knows how to handle both superior and inferior forces. (3) He will win whose army is animated by the same spirit throughout all its ranks. (4) He will win who, prepared himself, waits to take the enemy unprepared. (5) He will win who has military capacity and is not interfered with by the sovereign.Is victory in Iraq still possible? The answer is fundamentally three-fold.

Hence the saying: If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

- Enduring will.

- Articulating a Rule of Law.

- Effective administration of the law, equally among the governed.

Every conflict, especially asymmetric warfare (guerrilla war and terrorism), is unique (idiosyncratic). It is important, in a critical analysis of Iraq, that we conceptualize the type of conflict taking place there: the tactics and strategic goals of the guerrilla and terrorist forces.

The guerrilla's goal is to impose costs on the adversary in terms of loss of soldiers, supplies, infrastructure, peace of mind, and most importantly, time. In other words, guerrilla war is designed "to destroy not the capacity but the will" of the adversary.The tactics rely on their ability to attack using methods that not only take advantage of constraints placed on a government attempting to adhere to lawful combat, but are also intended to maximize civilian casualties and force the counterinsurgency into compromising combat situations that can be used as propaganda (i.e., using mosques for storing ordnance or as sniper positions). As Davida Kellogg wrote in Guerrilla Warfare, When Taking Care Of Your Men Leads To War Crimes:

Guerrilla warfare has at its very fond et origo an overarching strategy of turning any attempts on the part of opposing forces to adhere to the Law of War against them by using nominal civilians including women, the elderly, and even children, whom they know their enemy is legally and morally bound to treat as innocents, as un-uniformed irregulars. This "use of civilian clothing by (de facto) troops to conceal their military character during battle" is a war crime (U.S. Army Field Manual FM 27-10) because it violates the principle of distinction of the Hague Conventions which legally define belligerents. I know of no cases in which insurgents, or their superiors or governments, have been brought up on charges for this act, though perhaps we should start doing so, because it is by virtue of this deliberate blurring of the distinction between combatants and noncombatants that guerrilla warfare conduces to further war crimes against innocents.This type of warfare has long been problematic for Americans, and until the terror attacks on September 11, 2001, there was strong resistance to engaging in guerrilla wars. As General Paul Gorman, former SOUTHCOM commander, veteran of Vietnam, Korea, and unspecified intelligence work described it:

It is “inherently a form of warfare repugnant to Americans, a conflict which involves innocents, in which non-combatant casualties may be an explicit object. Its perpetrators are secretive, conspiratorial, and usually morally unconstrained. Their operations are the antithesis of respect for human rights.” There is also a suggestion that the enemy’s ruthlessness gives them an edge: “They can succeed if all they undertake is death and destruction, and yet they can impose on a defending government grave imperatives for restraint, heightened regard for human rights, creative reconstruction and societal reform under stress.”There is no cookie-cutter template from past insurgencies that can be applied to counterinsurgency operations in Iraq. James Dunnigan wrote for Strategy Page:

All of this makes Iraq a rather unique rebellion, guerilla operation, civil war, or whatever you want to call it. Comparisons to other guerilla wars will be difficult, because the size of the population supporting the guerrillas has a direct bearing on the chances of the guerrillas succeeding. In Iraq, the small portion of the population supporting guerilla operations indicates that the possibility of success is very low. But the fighting could go on for a while. The Malay insurrection of 1948-60 was carried out largely by the Chinese minority (37 percent of the population of 6.2 million). The Malay unrest, like that in Iraq, was pretty low key, with most of the population never bothered by the violence or military operations. The Malay situation eventually left 6,710 rebels and 3,400 civilians dead. The armed forces lost 1,865 (1346 Malayan and 519 British).The question that needs to be answered by critics of the surge in Iraq is, "How does increasing or decreasing the number of troops in Iraq contribute to our willingness to endure, the articulation of a Rule of Law, or the effective administration of that law equally across the population?"

Related:

Si vis pacem, para bellum

Iraq v2.0

Should We Stay or Should We Go?

Baghdad's Fissures and Mistrust Keep Political Goals Out of Reach

Iraqi politicians across the sectarian spectrum said their political process is being hijacked by American domestic politics. Pressured by congressional Democrats and growing antiwar sentiment at home, senior U.S. officials are growing impatient.Rick Moran writes:

Clearly, the government of Prime Minister Maliki doesn’t have time to affect the changes necessary that would lead to this reconciliation. By that I mean our efforts at improving security (the largest but by no means the only aspect of our new strategy) will only last as long as we have sufficient troops on the ground to carry out that mission. And the entire point of my article was simple; time is running out. Blame it on the press. Blame it on the Democrats. Blame it on Elvis. The fact is the American people have had enough. And what little support there is for our mission in Iraq will only lessen the closer we get to the 2008 election.I agree that the American people have run out of patience. Just check the polls on Iraq at PollingReport.com.

The Iraqi Security Forces must provide enough stability for Iraq's democratic political process. It will take decades to overcome the post-Saddam and historical scars that exist between competing Iraqi groups. However, there's a price to pay for pulling out of Iraq before the Iraqi Security Forces are able to provide that stability.

Kinda reminds me of The Clash's, Should I Stay or Should I Go?

UPDATE:

For an update on the Iraqi Security Forces, see BG Pittard's interviews from 27 April 2007:

Video: Brig. Gen. Pittard - Part 1

Talks to an ABC reporter in New York, N.Y., about the progress being made by the transition teams training Iraqi forces and the capability of Iraqi forces to take over their own security. Part 1 of 2.Video: Brig. Gen. Pittard - Part 2

Talks to an ABC reporter in New York, N.Y., about the rate of attrition in the Iraqi forces, the capabilities of Iraqi forces in combat, defending Iraqi borders, Iraqi equipment needs and the accountability of military leaders. Part 2 of 2.Video: Brig. Gen. Pittard

Talks to a Pentagon Channel reporter in Washington, D.C., about the progress of the Iraqi security forces, progress of the current troop surge and sectarian violence in Baghdad.Video: Brig. Gen. Pittard - Part 1

Talks to an NBC reporter in Baghdad about the progress of the Iraqi security forces, how sectarian conflict plays a role in the missions of the U.S. military, the stability of the Iraqi government and the security of the Iraqi borders. Part 1 of 2.Video: Brig. Gen. Pittard - Part 2

Talks to an NBC reporter about threats from Syria and Iran along the Iraqi borders, actions being taken to secure the borders, the progress of Iraqi security forces and the possible cuts in military funding. Part 2 of 2.

Raz Is Wrong

Guy Raz writes:

Members of the U.S. armed forces are prohibited from speaking out against the war in Iraq. The Uniform Code of Military Justice limits what soldiers may say about political issues.Note that Raz doesn't tell you where the UCMJ limits speech about political issues or specifically where in the UCMJ the U.S. armed forces have been prohibited from speaking out against the war in Iraq.

It gets better:

"You know this isn't really what we signed up to do. This isn't really what I believe America is about," an Army intelligence officer says, speaking from his base in Iraq.Wrong! But, hey, check it out for yourself.

Comments like this would land him in a military prison if he were identified.

DoD Directive 1344.10, "Political Activities by Members of the Armed Forces on Active Duty"

5 CFR 734: "Political Activity of Federal Employees"

Hatch Act for Federal Employees

UCMJ: Punitive Articles

Then, contact NPR's Ombudsman and tell them that Raz is wrong.

I also find it telling that Raz would mention this ...

It's known as the Appeal for Redress, and all of the signatories are active-duty servicemen and servicewomen.... but then fail to mention the Appeal for Courage.

Nearly 2,000 troops have signed the petition, most of them veterans of the Iraq war. There are about 1.4 million active- duty personnel in the U.S. military. [link added]

As an American currently serving my nation in uniform, I respectfully urge my political leaders in Congress to fully support our mission in Iraq and halt any calls for retreat. I also respectfully urge my political leaders to actively oppose media efforts which embolden my enemy while demoralizing American support at home. The War in Iraq is a necessary and just effort to bring freedom to the Middle East and protect America from further attack.Perhaps Raz should look into the partisan support of Hutto's Appeal for Redress?

Personally, I'm not a fan of either "Appeal." [UPDATE: That's too neutral. I would sign the Appeal for Courage and not the Appeal for Redress.] I am in favor of military members being able to express their opinions about the war, especially as citizens in letters to the editor and on their blogs. However, like Andrew J. Bacevich, I tend to worry about how politicians and the media treat such public expressions by members of the military on any political issues.

Implicit in the appeal is the suggestion that national-security policies somehow require the consent of those in uniform. Lately, media outlets have reinforced this notion, reporting as newsworthy the results of polls that asked soldiers whether administration plans meet with their approval.UPDATE: Journalists who wrote political checks

(D) CNN, Guy Raz, Jerusalem correspondent, now with NPR as defense correspondent, $500 to John Kerry in June 2004.Why am I not surprised?

Raz donated to Kerry the same month he was embedded in Iraq with U.S. troops for CNN. He also covered reaction to Abu Ghraib and President Bush's policies in the Middle East. In 2006, he returned to NPR, and covers the Pentagon.

"Yes, I made the donation," Raz said in an e-mail. "At the time, I was a reporter with CNN International based out of London. I covered international news and European Union stories. I did not cover US news or politics."

Both CNN and NPR prohibit political activity by all journalists, no matter their assignment.