The Surge as Stabilty and Support

During the Clinton administration, there was a debate over the primacy of stability and support operations and their impact on military readiness. The military was being significantly downsized, while at the same time, sent on an increasing number of these type of operations that committed us to rotating troops there for years. [See Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798-2001 (157KB pdf). It is not a complete list of military deployments. For example, not included on this list is Operation Safe Border/UN Military Observer Mission Ecuador - Peru which began in 1995 and ended in 1999. I do not know how many other deployments did not make the list, but it's probably more than just that one.]

This debate, famously articulated by former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright ("What's the point of having this superb military that you've always been talking about if we can't use it?" - here and here) and again as the "Clinton Doctrine" ... was not a new debate. As Gen. John M. Shalikashvili explained to the Robert R. McCormick Tribune Foundation, George Washington University, Washington, May 4, 1995:

But the debate has changed in one way. During the Cold War it was those on the left criticizing the Cold Warriors for taking too many risks; for overcommitting our lives, our treasures and our morality; for overextending our power and our commitments for the purpose of containing communism. Today, of course, that is different. It is those on the right who are castigating those on the left for allowing their humanitarian and their moral impulses to places where our interests, in fact, are thin or nonexistent. So the core debate has not ended at all. The real issues have not been resolved. Only the tables have been turned. [emphasis added]Military force structure during the Clinton administration was being driven by a sense that after the end of the Cold War, "everything's changed". The basis for our military force structure before the end of the Cold War was our national security requirement to fight and win two regional wars (2MTW). The 2MTW concept was discarded as archaic Cold War thinking. We no longer needed to structure the military to fight one "high-intensity" conflict [Fulda Gap] and one "medium-intensity" conflict [Korea or Iraq] simultaneously. We no longer perceived a threat from an adversary that could fight a "high-intensity" war. Instead, we wanted a "peace dividend". We wanted a smaller military. We wanted a balanced budget.

So the risk assessment for the threats to the nation evolved. Instead of simultaneously fighting and winning a high-intensity and a medium-intensity conflict, it became two medium-intensity conflicts. Then it became two "near simultaneous" medium-intensity conflicts: win in one and hold in the other. Asymmetrical warfare and transformation became the cause célèbre in force structure policy. Transformationalists wanted a versatile military that could do everything - using technology as a force multiplier - and be deployable from the U.S. to anywhere in the world (meaning lighter and more modular). American bases abroad became another anachronism of Cold War thinking. For additional insight into how transformation influences force structure planning, I recommend Col. Wolborsky's Swords Into Stilettos: The Battle Between Hedgers and Transformers for the Soul of DoD (219KB pdf) and Tom Barnett's Op/Ed for The Command post.

A useful metaphor for understanding American foreign policy during the 90s and the restructuring of our military forces, as well as their employment throughout the world, is Time's Arrow:

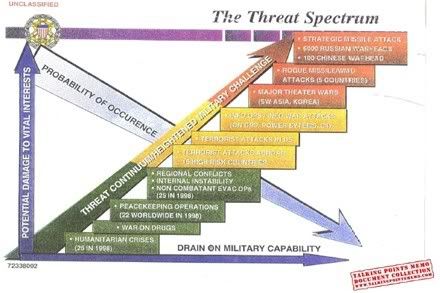

In the post-Cold War era, there has also been a renewed emphasis on time's arrow in the international system against the backdrop of unique trends such as those concerning global transparency and global environment. These trends are the cumulative results of the forces unleashed by the revolutions in communications, information, transportation, and technology that predated the end of the Cold War. Theorists as early as the 1970s argued that with the expansion of commerce as a result of these forces and trends, relationships based on cooperation and integration were becoming at least as important as traditional geopolitical competition. In the intervening years, liberal analysts have concluded that the unique, linear evolution of complex economic interdependence fosters peace by causing trading to be more profitable than war. Interdependent states, in other words, would rather trade than invade--a conclusion at the systems level of analysis for these theorists reinforced by the cumulative learning at the individual and state levels focused on changing values and what is perceived as the irreversible victory of liberal capitalism. From this perspective, war is a particularly counterproductive way for any rational nation-state to achieve the central goals of prosperity and economic growth.[49]In April 2004, Josh Marshall linked to the Threat Spectrum shown below (click for larger view, 273KB pdf).

It is, however, a perspective that overreacts to forces and trends in time's arrow while ignoring the immediate and long-term implications of time's cycle. In the short-term, it is not economic interdependence that has brought about great power peace. Instead, it was the bipolar peace of the Cold War, founded on rivalry and fear of nuclear war, not desire for profit, that induced the cooperation that made economic interdependence safe and therefore possible. In a world in which there is little likelihood of large-scale conflict, states are less concerned about the dependencies that such interdependence creates and about the relative economic disadvantages that open markets produce.[50] At the same time, as leaders in the current transition period react to a variety of "unique" ethnic and religious strife throughout the globe, the Cold War is a useful reminder that during the superpower stability of that long twilight conflict, no such condition occurred for very long in the so-called Third World, a categorization of nation-states that even owed its origins to the bipolar nature of the international system. In that world, the absence of superpower war was not synonymous with global peace; nor was the absence of system transformation through war translated into global stability. Instead, recurrent violence in an unstable "peripheral" system occurred alongside a stable "central" system, with an estimated 127 wars and over 21 million war-related deaths taking place in the developing world during the Cold War.[51]

Marshall's purpose at the time was to demonstrate that terrorism was a known threat prior to Sept. 11, 2001. Relevant to this debate is Marshall's statement:

This is a strategic argument about where our chief vulnerabilities are and where and how our defense resources should be applied -- not a question of who saw what Presidential Daily Brief or what was contained in it.This chart has, in fact, been around for years. You can see on the chart that statistical information is for 1998. Sen. Levin referred to it in 2000 as a document prepared in 1999:

Last year, the Joint Chiefs prepared a diagram demonstrating the full spectrum of threats to our nation's security and prioritizing the probability of occurrence of these various threats. This threat spectrum demonstrated that the threats which carry the greatest potential damage to our vital interests, such as strategic missile attack and major theater wars, are also the least likely to occur. The more likely threats to our national interests will come from regional conflicts due to ethnic, religious or cultural differences, or from terrorism.The Threat Spectrum was referred to again during the 2001 missile defense debate. For example, during Senate Armed Services Committee testimony on July 12, 2001, by then Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz and Lieutenant General Ron Kadish and again by Ted Koppel during an interview with Wolfowitz on July 24, 2001. All of these instances precede the Sept. 10, 2001, reference by Senator Biden that Marshall quotes.

My purpose for using the Threat Spectrum is three-fold: 1) The document has bona fides, as demonstrated by these references; 2) It is an excellent visual for thinking about how to size and structure the force to defeat threats that are considered a low probability of occurence, but high drain on military capability versus more likely threats; and 3) It visually makes a sharp contrast with models used during the Cold War.

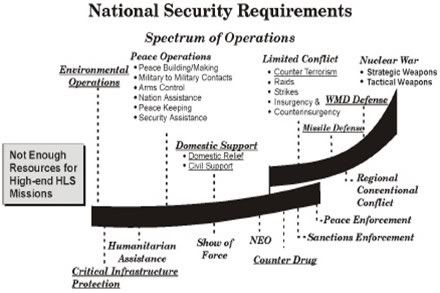

For example, compare the Threat Spectrum with the Spectrum-of-Conflict Model (shown below).

This was a predecessor to the Threat Spectrum and described in Assessing New Missions.

The spectrum-of-conflict model was used in a number of DOD publications and briefings during the Cold War, particularly during the 1980s.What I find instructive, in contrasting the two charts above, is how thinking about military contingencies become more detailed - more complex - after the Cold War ended. How does the military need to be structured based on the type and probability of these diverse threats? What skills are needed to fight and win across the Threat Spectrum?

...

On the surface, the spectrum-of-conflict model is an understandable, idealized representation of the frequency that military force might be used in differing but related activities. Out of context, it could be swiftly dismissed as merely academic, a clever illustration. But, in reality, its use to describe U.S. military activities illustrates specific assumptions about how military power should be used, as well as specific sets of priorities for the missions that the military is designed to carry out.

In March 2001, Lieutenant Colonel Antulio J. Echevarria II wrote a prescient monograph, The Army and Homeland Security: A Strategic Perspective, "investigat[ing] the Army’s role in homeland security from a strategic, rather than a legal or procedural perspective." The reason I find this monograph important is, before Sept. 11, 2001, Homeland Security (HLS) was not a contingency or "threat" that got much visibility. There was an assumption, based on conventional wisdom, that the battle would be fought abroad.

Some key graphs from Echevarria's monograph:

... policymakers must now focus as much on possibilities as on probabilities, as much on vulnerabilities as on threats. Put differently, an effective homeland defense might require treating vulnerabilities as seriously as confirmed threats under the traditional reckoning.One more chart, also from Echevarria's monograph. Take note of the list (spectrum) of operations our military currently performs:

...

In the absence of an authoritative definition, the Army has rightly developed and tentatively approved the following “all-hazards” definition in its HLS: Strategic Planning Guidance (Draft dated Jan. 8, 2001):Protecting our territory, population, and infrastructure at home by deterring, defending against, and mitigating the effects of all threats to US sovereignty; supporting civil authorities in crisis and consequence management; and helping to ensure the availability, integrity, survivability, and adequacy of critical national assets.

Dag Hammarskjold, former UN Secretary-General, said, "Peacekeeping is not a soldier's job, but only a soldier can do it." Perhaps it's the same with stability and support operations such as nation building, which often goes hand-in-hand with peacekeeping. Promoting tolerance and democracy after defeating an intolerant dictator may not be a soldier's job, but soldiers have always been the ones called upon to do it.

Previous:

The Surge as Foreign Internal Defense

Would Sun Tzu Surge?

Si vis pacem, para bellum

Iraq v2.0

No comments:

Post a Comment