The Surge as Foreign Internal Defense

We didn't have the right troops in Iraq after Saddam's regime fell because we didn't have a single, coordinated plan across government agencies - and with our allies and international non-government organizations - for filling the vacuum and stabilizing Iraq that was ready to implement. As a result, we failed to interdict, and were slow to react to, the insurgency by Baathist remnants and the influx of jihadist terrorists. We've been playing catch-up ever since.

President Bush stated the strategic plan at the United States Army War College on May 24, 2004, more than a year after declaring major combat ended:

There are five steps in our plan to help Iraq achieve democracy and freedom. We will hand over authority to a sovereign Iraqi government, help establish security, continue rebuilding Iraq's infrastructure, encourage more international support, and move toward a national election that will bring forward new leaders empowered by the Iraqi people.This plan had two thrusts, political and military, and they were not independent of each other. The political process consisted of interim sovereignty, elections for a transitional national assembly which drafted a constitution, put the draft constitution to the Iraqi people in a referendum in 2005 and elected a permanent government by December 2005.

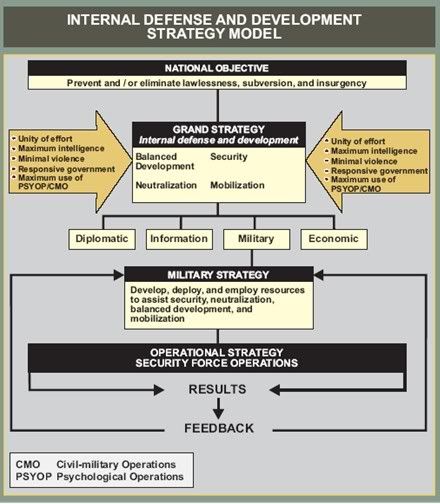

The military thrust is foreign internal defense (Joint Publication 3-07.1, Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Foreign Internal Defense (FID),1.6MB pdf), which includes, but not limited to, counterinsurgency, training security forces, rebuilding infrastructure and, as a result, maintain the host nation's (HN) sovereignty and legitimacy. The graphic at right (click for larger image) shows how military FID strategy is determined by the HN's Internal Defense and Development (IDAD) planning. In order for us to judge the type and number of troops needed, we can look to Chapter III of JP 3-07.1, which lists planning imperatives for FID [all emphasis in original, unfamiliar acronyms expanded in brackets]:

The military thrust is foreign internal defense (Joint Publication 3-07.1, Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Foreign Internal Defense (FID),1.6MB pdf), which includes, but not limited to, counterinsurgency, training security forces, rebuilding infrastructure and, as a result, maintain the host nation's (HN) sovereignty and legitimacy. The graphic at right (click for larger image) shows how military FID strategy is determined by the HN's Internal Defense and Development (IDAD) planning. In order for us to judge the type and number of troops needed, we can look to Chapter III of JP 3-07.1, which lists planning imperatives for FID [all emphasis in original, unfamiliar acronyms expanded in brackets]: - Maintain HN Sovereignty and Legitimacy. If US military efforts in support of FID do anything to undermine the sovereignty or legitimacy of the HN government, then they have effectively sabotaged the FID program. The FID program is only as successful as the HNs IDAD program.

- Understand long-term or strategic implications and sustainability of all US assistance efforts before FID programs are implemented. This is especially important in building HN development and defense self-sufficiency, both of which may require large investments of time and materiel. Comprehensive understanding and planning will include assessing the following:

- The end state for development.

- Sustainability of development programs and defense improvements.

- Acceptability of development models across the range of HN society, and the impact of development programs on the distribution of resources within the HN.

- Second-order and third-order effects of socio-economic change.

- The relationship between improved military forces and existing regional, ethnic, and religious cleavages in society.

- The impact of improved military forces on the regional balance of power.

- Personnel life-cycle management of military personnel who receive additional training.

- The impact of military development and operations on civil-military relations in the HN.

- Tailor military support of FID programs to the environment and the specific needs of the supported HN. Consider the threat as well as local religious, social, economic, and political factors when developing the military plans to support FID. Overcoming the tendency to use a US frame of reference is important because this potentially damaging viewpoint can result in equipment, training, and infrastructure not at all suitable for the nation receiving US assistance.

- Ensure Unity of Effort. As a tool of US foreign policy, FID is a national-level program effort that involves numerous USG [US Government] agencies that may play a dominant role in providing the content of FID plans. Planning must coordinate an integrated theater effort that is joint, interagency, and multinational in order to reduce inefficiencies and enhance strategy in support of FID programs. An interagency political-military plan that provides a means for achieving unity of effort among USG agencies is described in Appendix D, Illustrative Interagency Political-Military Plan for Foreign Internal Defense.

- Understand US Foreign Policy. NSC [National Security Council] directives, plans, or policies are the guiding documents. If those plans are absent, JFCs [Joint Force Commanders] and their staffs must find other means to understand US foreign policy objectives for a HN and its relation to other foreign policy objectives. They should also bear in mind that these relations are dynamic, and that US policy may change as a result of developments in the HN or broader political changes in either country.

FID in Iraq supports the process of midwifing an Iraqi government which is seen as legitimate by the Iraqi people. The size of the force must be small enough, and its employment restricted enough, to make it incumbent on the Iraqi people to accept responsibility for their security.

The military mission has not changed.

Previous:

Would Sun Tzu Surge?

Si vis pacem, para bellum

Iraq v2.0

No comments:

Post a Comment